I hardly consider myself a paragon of self-control – we all have our vices and addictions, whether it’s alcohol, social media, or sugar. It can be incredibly difficult sometimes to muster the self-control to rein in these impulses, but certain shifts in mindset can provide a valuable tool.

A year or two ago I read a book by Howard Rachlin called the Science of Self-Control. At the time I was smoking and drinking more than I wanted, and wanted to curtail it. I had been reading Rachlin’s book, and he discussed a few concepts that reframed my view of addiction in a meaningful way – all of it was things I intuitively knew, but by defining what happened it helped identify what I was constantly doing. Many of us have a way we rationalize or intuitively approach addictive behaviors, or do things when we should ‘know better’ in moments of low willpower. He describes this phenomenon as ‘Ambivalence.’

Ambivalence is the coexistence of opposing feelings. In the case of addictions it is usually clear where the conflict is, particularly among people who are trying and sometimes failing to curtail the behavior. There is the long-term, top-down desire to stop the behavior, whether it’s for our health, our social life, or some other reason. Yet there is also the desire of our immediate self to gratify whatever addiction we have – to satisfy a craving, to have a fun night, to relax. Ambivalence manifests clearly when we set an alarm to wake up in the morning, and then hit snooze – the self that sets the alarm and the self that switches it off are acting in opposition to one another, and we often then proceed to rationalize this ambivalence with an excuse – you slept poorly, you’ve got a busy day ahead of you and need the rest. This ‘two selves’ idea, that you have opposing forces in you both with their own desires, is important – both are you, and in a sense, both are rational.

When you’re operating on a narrow timeframe – let’s say the next twenty minutes, having a drink is pretty much all benefit. Your mood and sense of well-being is elevated, and the consequences of a hangover are not within your timeframe. In this narrow window, drinking is perfectly rational – why wouldn’t you elevate your mood and enjoy a drink? Of course, we humans have the ability to see further into the future than the next twenty minutes. That elevated mood is brief, gives way to sluggishness, and the next day a hangover awaits. Repeat the ceremony of getting outrageously drunk night after night and your health will deteriorate, your liver will fail, and you’ll die younger than you would have had you abstained or drank more responsibly. We can acknowledge that its in our long term interest to abstain, but our short term interest to indulge, and that is the source of our ambivalence, anxiety, and struggle.

Rachlin outlines the phenomenon where we enjoy the sum of one activity more than several repetitions of another, but in a narrower timeframe prefer the briefer activity. The example he uses is the difference between listening to a 1 hour symphony versus listening to 2 minute songs. Many people may prefer to listen to a 2 minute song than 2 minutes of a symphony, but may prefer the hour of symphony to an hour of 2 minute songs. Overcoming this can be problematic – our initial baseline feedback tells us that the 2 minute songs are more satisfying, even if perhaps we know that it’s a cheap satisfaction. This explains our impulse towards many easier, more trivial pleasures – to constant scrolling on social media as opposed to reading a book, or watching TV instead of working on a project we’ve been meaning to do.

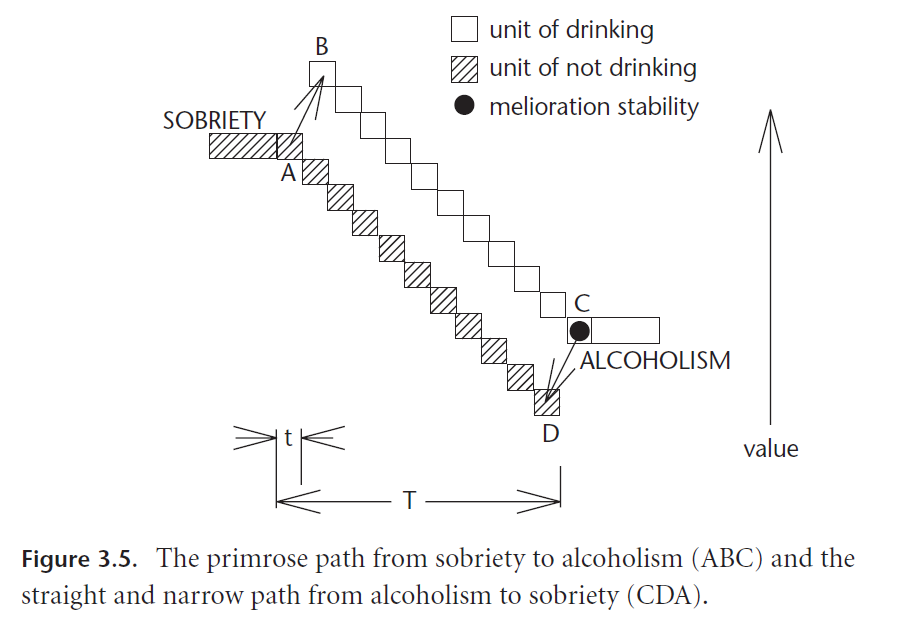

The Primrose Path relates closely to this idea – it can be visualized as a downward staircase of units of behavior – let’s say, each alcoholic drink. Each drink has a utility, such as pleasure. The bad behavior will cause an initial spike that brings you above baseline utility, but have a corresponding drop that brings you below it – the intoxication, hangover, and other negative health effects. The next bad behavior will elevate you again, but this time just to baseline, and then drop. The next elevation won’t even reach baseline, yet it will be better than where you were before you had the drink… And so on, and so on. This choice of the highest value ‘unit’ in a given time is known as ‘melioration’. It’s a consequence of short term thinking, but that isn’t to say that the pleasure (or, often in the case of addictions, the alleviation of pain) is irrational, merely short-sighted. Scratching an itch – often used as a metaphor for addiction – is itself an excellent example of the Primrose Path, as many of us who itch too much can attest. The satisfaction of scratching only worsens the itch, and introduces pain as you damage your skin, yet at any given moment, it remains so desirable to simply scratch the itch.

A game example of the Primrose Path

- You have two buttons – Y and X.

- Generally 50-100 trials (presses)

- The below rules are not known to the participants:

- Each choice of Y adds N points

- Each choice of X adds N+3 points

- N at each choice is equal to the number of the Ys in the previous 10 choices.

If you play this game you’ll quickly notice a pattern – pressing X repeatedly will pull you ahead of Y short term, and in each individual ‘round’ is in fact the best choice. When N is 0, X is the best choice. When N is 10, X is still the best choice. Yet by choosing X, you are penalizing your next round – do it enough, and you’ll be worse off than if you simply mashed Y.

Most of us are intuitively aware of the concept of the Primrose Path, but having it spelled out, at least to me, proved a valuable insight during moments of craving or short-term desire. It helped mitigate some of the shame you feel that you are being stupid or irrational – you’re not, at least not exactly – you’re in a conflict between two selves with distinct goals. You’re experiencing ambivalence. It is also comforting to know that if you are already partway down the path or – god forbid – near the bottom, despite the fact that the immediate effects of addressing the problem result in greater discomfort, it eventually will stabilize at a higher baseline. It will get better.

What can you do about it?

There are several methods you can practice to help undercut the Primrose Path problem. The main danger of the Primrose Path is the fact that in the short term, the benefits outweigh the cost of bad behavior – the pleasure derived from the action is often immediate, while the consequences are far in the future and therefore discounted. By instituting an immediate penalty for your bad behavior – for example, a financial penalty donated to charity – you introduce an immediate sting which makes the immediate utility less desirable. In a sense, it brings that discounted penalty forward into your immediate time-frame, and make the bad behavior less desirable.

This payment system, when paired with a system of social accountability, can be invaluable for keeping you on track. This is a method that myself and a few others have been using for years – there are still hiccups, but the cost of the hiccups usually means you stop at a step or two down the stairs rather than a precipitous tumble towards rock-bottom. We’ve since created a Discord server to build a network of people trying to improve their self-discipline by setting wagers against their goals, you’re welcome to join it and give it a try. You can join with this link.

Works Referenced:

Rachlin, Howard – The Science of Self Control – Amazon link