The Social Influence Effect

“You are the average of the top 5 people you spend the most time with.” This phrase strikes a chord with many of us—even if it’s surely a crude heuristic rather than a scientific law, it carries an intuitive truth. Yet within this simple observation lies a cycle: our social environments shape our character, our character determines our actions, and our actions reshape those environments. This cycle can spiral upward toward excellence or downward toward hell.

Most people naturally adopt the behaviors and habits of those around them, for better or worse. If your top 5 friends are drinking buddies, you’re certainly more likely to spend more time drinking. If they’re all dedicated to Jiu Jitsu, you may well spend more time on the mats than at the bar. Your conversations shift from slurred bar talk to discussions of arm-bar techniques, upcoming competitions, and training injuries.

This influence extends to all social circles. If your closest companions are entrepreneurs, programmers, actors, bureaucrats, or some mixture of these, the content of your life inevitably shifts. And it seems self-evident that this change of content affects your outcomes. Unless you believe you’re somehow immune to social influence, the conclusion is straightforward: who you spend time with shapes who you become.

The Portfolio of Friends Fallacy

Yet this insight has often been interpreted in a troublingly transactional way. Many people conclude that to better their lives, they must replace their friends with “higher quality” people. Like an investment portfolio, bad investments are cut to favor new more promising prospects. By raising the average quality of their peers, the math checks out that they too will improve. There’s some truth here—spending more time with athletes than alcoholics will likely result in more hikes than pub-crawls. But this approach misses something fundamental about the nature of friendship and influence.

Consider the damage one gossip can do in a workplace or friend group, gleefully sowing distrust and suspicion that destroys otherwise healthy relationships. Imagine an entire culture of gossips, each hissing behind the backs of others despite their passive-aggressive faux-smiles. Now imagine a world where such people held all the power, including the power of life and death. Psychologist Jordan Peterson takes these vicious aspects of a society – those of deceit and resentment – as a serious forecast for an authoritarian society, one where nobody says what they mean, and nobody means what they say, where baseless accusations can mean imprisonment and death. It’s a manifestation of how negative traits compounds socially—from interpersonal toxicity to societal corruption.

Every small action we take has the potential to ripple out and amplify, forming feedback loops that can become deafening. Peterson warns often in his writing and lectures about the archetypal Cain, the embodiment of bitterness, resentment and deceit that has cascaded down from its biblical origins of brother slaying brother to contaminate mankind ever after. He cautions us that authoritarian tyranny is sustained by the population, not only the tyrant. A population that self-polices out of mutual fear and suspicion, that silences truth in favor of collective lies. Hell. Indeed, only a truly virtuous relationship is safe from the venom of deceitful – if you have such character that those around you know you say what you mean and mean what you say. If you have trust and faith, built by genuine camaraderie and regular proof.

The Science of Social Contagion: How Behaviors Spread Through Networks

The adage about becoming the average of the five people closest to you is supported by substantial scientific research in a field known as social contagion theory – but what is alarming (or perhaps encouraging) is the fact that the effect spreads far beyond those closest to you. Social contagion theory explores how behaviors, emotions and ideas can spread through a network – this is what some people have taken to calling a ‘mind virus’ in its negative form. And indeed, there is a considerable dark side to social contagion.

The Christakis-Fowler Studies

Compelling scientific evidence for social contagion comes from the work of Dr. Nicholas Christakis and Dr. James Fowler, who published a series of influential studies beginning in 2007. Using data from the Framingham Heart Study, which tracked over 12,000 people across 32 years, they discovered that obesity spreads through social networks—a person’s chance of becoming obese increased by approximately 57% if they had a friend who became obese during a given time interval.

Even more remarkable, the contagion effect extended up to three degrees of separation. As Christakis and Fowler documented, “a person’s risk of obesity went up about 10 percent even if a friend of a friend of a friend gained weight.” This was true even after controlling for the fact that friends may choose similar friends. Rather, it demonstrated genuine social transmission of behaviors.

This pattern wasn’t limited to obesity. The researchers found similar network effects for smoking cessation, alcohol consumption, and—perhaps most importantly for our discussion—happiness and emotional states. Their research showed that happiness spreads between next-door neighbors, siblings living nearby, and spouses. We’ll get to that soon, but let’s start with the grizzly warning, shall we?

The Dark Side: Negative Contagion

Research during the COVID-19 pandemic revealed how negative emotions can rapidly propagate through social networks, particularly on social media platforms. Studies published in Frontiers in Psychology demonstrated that “the stimulation and emotional contagion of unjust and immoral events can trigger negative emotions such as anxiety, anger, and sadness”. These emotions, once activated within a network, can spread widely and intensify over time.

Perhaps one of the most well-documented examples of negative social contagion occurs with eating disorders among adolescents, particularly girls. Paxton, Schutz, Wertheim, and Muir (1999) found that within friendship cliques of adolescent girls, there were striking similarities in body image concerns, dietary restraint, and extreme weight-loss behaviors. Once again the researchers demonstrated that these weren’t cases of similar people finding each other—the behaviors were actively spreading within established social groups. Jarvi, Jackson, Swenson, and Crawford (2013) documented extensive evidence that self-harm behaviors can spread through peer groups via social learning, with adolescents being particularly vulnerable to this influence. Their review found that exposure to self-injury through peers was a significant risk factor for engaging in similar behaviors, with studies showing that between 16-20% of adolescents who self-harm report learning the behavior from friends.

This contagion effect has only intensified with social media. When considered from the perspective of an infectious disease, you might conclude that much of our social media environment has long since become septic. Even contact with such environments can be poisonous.

People naturally mirror the emotional expressions and behaviors of others, and through repeated exposure, begin to internalize these states and norms. This can create dangerous feedback loops in social environments—whether digital or physical—where negativity begets more negativity.

The Bright Side: Prosocial Contagion

Just as negative behaviors can spread, so too can positive ones. Research on a phenomenon called “elevation”—a unique emotion experienced when witnessing moral excellence or virtue—shows that this feeling motivates people to engage in their own prosocial behaviors. Social Psychologist Jonathan Haidt describes the emotion as “… a warm or glowing feeling in the chest, and it makes people want to become morally better themselves”.

The evidence for elevation’s prosocial effects is encouraging. In a series of studies by Algoe and Haidt (2009), participants who experienced elevation were significantly more likely to report prosocial motivations than those experiencing other positive emotions. When recalling instances of witnessing moral excellence, 43% of elevation participants reported wanting to help others, compared to just 3-5% of participants recalling joy or other positive experiences. Even more striking, 71% of elevation participants reported “moral motivations” like wanting to become better people or emulate virtuous behavior, compared to only 3% in the joy condition.

Laboratory studies further strengthen this connection. When shown videos depicting acts of moral excellence (such as Mother Teresa’s work), participants reported a significantly stronger desire to help others (2.62 on a scale from -4 to +4) compared to those who watched amusing or otherwise positive but non-elevating content (0.44). This translated to real behavioral changes—in one study, people experiencing elevation were more likely to volunteer for a humanitarian organization than control groups.

“If elevation increases the likelihood that a witness to good deeds will soon become a doer of good deeds, then elevation sets up the possibility for the same sort of ‘upward spiral’ for a group… frequent good deeds may have a type of social undoing effect, raising the level of compassion, love, and harmony in an entire society.”

It’s rare I see “Moral beauty or virtue” called out in scientific research, and I always get a bit giddy at the terms. As a bit of an Aristotle fanboy, I can never resist the opportunity to draw things back to virtue ethics and eudaimonia – you can tell by the name I chose, I’m sure. I’ve written plenty the concept of eudaimonia over the years, and the scientific backing for positive social contagion through elevation gives another strong argument in favor of the cultivation of your own virtue. This should not be mistaken for ‘virtue signaling’ or moral policing – I’m far more concerned with genuine self-improvement and leading by example.

Aristotle’s Wisdom: The Three Types of Friendship

This modern wisdom about social influence echoes what philosophers have understood for millennia. Aristotle, in his Nicomachean Ethics, spent considerable effort (rather dryly) exploring the philosophical grounding of our morals and virtues. And he devoted more space to friendship than any other virtue—he considered it essential to the flourishing life and a functioning state. Insofar as man was a political animal, bonds of affection were fundamental glue for the function of any group. Far from seeing friendship as merely a means of self-improvement, Aristotle recognized it as a fundamental human good: “For no one would choose to live without friends, despite having all the rest of the good things.”

Aristotle identified three distinct types of friendship: those based on utility (where people associate for material benefit), those based on pleasure (companions who enjoy each other’s company), and those based on virtue (friends who admire and inspire each other toward excellence). This third category—friendship based on virtue—represents the highest form of human connection in Aristotle’s ethical framework, and the optimal opportunity for elevation.

“Perfect friendship is the friendship of men who are good, and alike in virtue; for these wish well alike to each other in so far as they are good, and they are good themselves.”

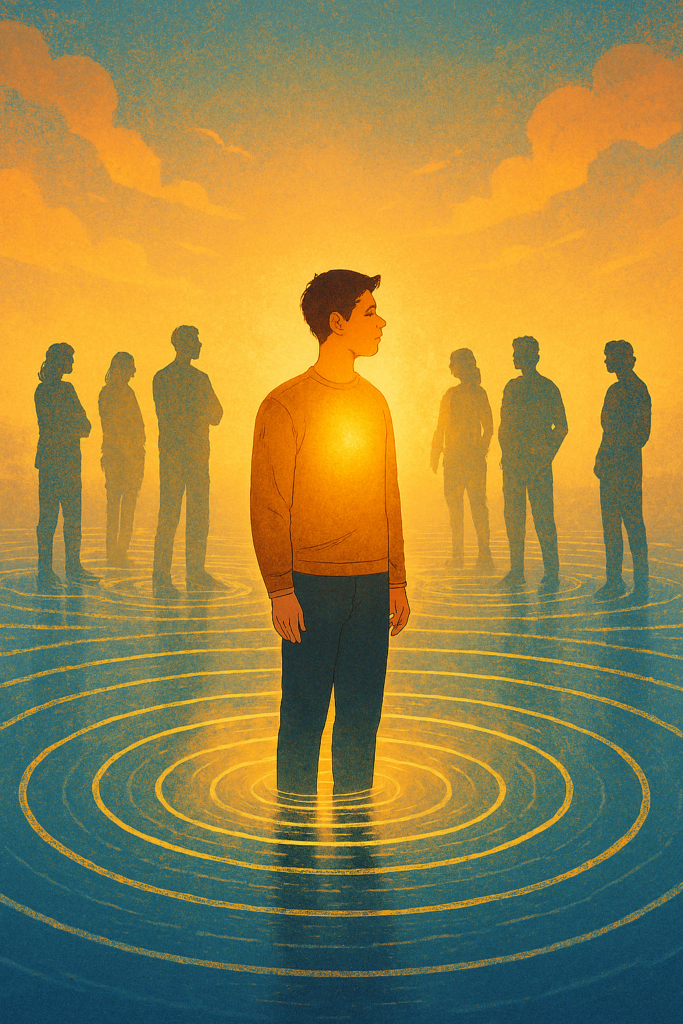

Inverting the Equation: From Being Influenced to Becoming an Influence

This deeper understanding of social contagion, virtue and friendship offers an alternative to the cold math suggested by the modern quote. Let’s invert the wisdom for a moment: It’s common but foolish to think influence only flows one way, that you are malleable but others are static. If you are the average of the five people you spend the most time with… doesn’t it also follow that you are surely part of that average for many other people?

George Mack provides a useful frame for understanding this dynamic through the concept of agency. He defines agency as a spectrum: low agency is “life happening to you,” while high agency is “you happening to life.” Applied to our discussion, “You are the average of the top 5 people you spend your time with” represents people happening to you. In contrast, “You contribute to the average character of those you associate with” represents you happening to people. The choice between these perspectives is essentially a choice about whether you will be a passive recipient of social influence or an active agent in your social ecology. It also speaks to how much moral responsibility you have for your own behavior.

What if, rather than coldly cutting people out of your life like unwanted fat or casting about for “more useful” friends, you recognized the opportunity for your own actions to transform your network? What if your decision to quit drinking and schedule hikes instead of bar-hops had the potential not just to improve your own life, but the lives of all your friends, and their friends, and their friends’ friends—creating a virtuous cycle that compounds over time? What if the healthiest social circles weren’t created by social climbers who ruthlessly vetted and pruned their connections, but by those who actively cultivated and elevated them? Through this network effect, some positive change in your own life can have an immeasurable positive influence on the world. And yes, the inverse is also true.

Cultivating Virtue: The Ripple Effect of Personal Excellence

When you cultivate qualities in yourself, you naturally seek and inspire these qualities in your friends, good or bad. If you treat friends as tools, expect to be treated likewise. As a person of virtue, you won’t be inclined to callously discard relationships, though sometimes judicious distance may be necessary—some people genuinely do not share your values and have no desire to participate in the circle you wish to cultivate. In such cases, it is better for both of you to part ways. But as a rule, by developing qualities in yourself that you admire, you elevate and influence those around you. Every time you achieve a goal or behave in a way others might have thought impossible, you remind them what’s possible.

The real wisdom isn’t just to surround yourself with “better” people, but to become the kind of person who is capable of cultivating their own betterment, which will naturally shift the quality of your relationships in a virtuous cycle. True friendship, according to Aristotle, is a relationship between equals. You are not groveling at the feet of superiors in hope of inheriting their greatness—that makes you a sycophant, not a friend. Nor are you standing above moral “lessers” radiating greatness for their benefit—that narcissism breeds only contempt and resentment, not friendship. Friendships of virtue require speaking and acting freely with one another, forgiving easily, and focusing on what matters. They involve a genuine mutual interest in one another’s wellbeing and an exchange of value (and values)—a faith that those around you have something to offer you, and you have something to offer them. It requires an admiration and encouragement of their good qualities, and the considerate discouragement of their vicious ones. Few people are elevated by condescending charity or moralistic nagging; they are elevated because they are inspired by love and admiration—philia as the Greeks would put it.

This cycle—from social environment to individual character to actions that reshape environments—operates at multiple levels. At the personal level, it determines our habits and virtues. At the interpersonal level, it governs the quality of our friendships and relationships. At the societal level, it influences culture and institutions. In the end, you don’t just become the average of the five people closest to you—you create the average.

References

Aristotle. (2009). The Nicomachean Ethics (D. Ross, Trans.). Oxford University Press. (Original work published ca. 350 BCE)

Algoe, S. B., & Haidt, J. (2009). Witnessing excellence in action: the ‘other-praising’ emotions of elevation, gratitude, and admiration. Journal of Positive Psychology, 4(2), 105-127.

Christakis, N. A., & Fowler, J. H. (2007). The spread of obesity in a large social network over 32 years. New England Journal of Medicine, 357, 370-379.

Chen, X., et al. (2022). Emotional contagion: Research on the influencing factors of social media users’ negative emotional communication during the COVID-19 pandemic. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 931835.

Haidt, J. (2000). The positive emotion of elevation. Prevention & Treatment, 3(1), Article 3.

Jarvi, S., Jackson, B., Swenson, L., & Crawford, H. (2013). The impact of social contagion on non-suicidal self-injury: A review of the literature. Archives of Suicide Research, 17(1), 1-19. https://doi.org/10.1080/13811118.2013.748404

Paxton, S. J., Schutz, H. K., Wertheim, E. H., & Muir, S. L. (1999). Friendship clique and peer influences on body image concerns, dietary restraint, extreme weight-loss behaviors, and binge eating in adolescent girls. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 108(2), 255-266. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-843X.108.2.255

Peterson, J. B. (2023). We Who Wrestle with God: Perceptions of the Divine.

Thomson, A. L., & Siegel, J. T. (2019). Elevation, an emotion for prosocial contagion, is experienced more strongly by those with greater expectations of the cooperativeness of others. PLOS ONE, 14(12), e0226071.

Mack, George. High Agency. (2025). https://www.highagency.com/

Prinzing, M. M., et al. (2021). How the affective quality of social connections may contribute to public health: Prosocial tendencies account for the links between positivity resonance and behaviors that reduce the spread of COVID-19. Affective Science, 2, 379-390.