There’s a famous saying in the media studies world, parroted a lot, though when you hear it for the first time, it sounds a little enigmatic. “The medium is the message.” Coined by the philosopher Marshall McLuhan, it definitely sounds a bit like philosopher-talk. When I was in university I took a first year communications class – my professor assigned a book called The Shallows by Nicholas Carr, and it had a profound impact on how I viewed the effects of the internet on my thinking.

Carr takes the time to unpack the famous saying. What does that mean, that “the medium is the message”? Well, intuitively we tend to think that the medium conveys the message. If the message is “Hello”, you might hear it through the medium of speech, or writing. It might be a text message, a parcel of code like ‘Hello World’, or through loudspeakers outside your window at three in the morning. In a sense the message is the same, though we can all agree that the medium by which its conveyed to us can change the content anyhow.

As messages grow more complex, along with the media we use to convey them, the ability for the media to affect the message in both overt and subtle ways grows. Consider a work of Shakespeare. There are considerable differences in the experience of reading Shakespeare versus seeing it performed. There are also differences between how Shakespeare would be performed on stage, on the radio, or in a movie. Each medium has something unique to offer, a certain flavor. Reading it allows you to stop and re-read, to contemplate it, to linger on a certain passage you didn’t quite understand. Its performance on stage allows for the behavior of the actors to fill in gaps, to portray their moods and intentions through their expression and movement – it also allows you to become part of an audience all around you, intuiting humour when they laugh, or suspense from their tension. Film changes things again, allowing for intimate closeups on facial expression that would have been impossible even in real life, or carefully crafted cinematography using light, camera angles and music to engineer certain emotions.

And the internet has produced its own unique medium. At first a domain largely of text, and ‘book-like’ in nature, it has nonetheless never simply been a book. Even from its early days, the hyperlink provided a new tool that set it apart it from physical media. Anyone who has gone down a Wikipedia rabbit hole understands that an online, hyperlinked encyclopedia is not the same thing as a paper one. The internet, as a medium, thrives on distraction. It drags our attention from one thing to the next, prompting us with new choices – whether those choices are to follow a hyperlink, change to a new browser page, switch to a different type of media entirely (such as from text to video), or sophisticated combinations of each. Multitasking becomes effortless – though it remains costly regardless of how easily we can do it.

Consider this article – it is not a book, and it’s not much like a conventional essay, either. It’s written for – ironically – publication on a website called ‘Medium’, where the time a paying subscriber views the article generates money. What does this mean for the writing process? It means that I have a financial incentive to first grab your attention – so that you open the article – and then hold your attention, so that you read it. And this principle is pretty central to most online content. Attention is money, and it’s metered out in seconds and fractions of cents, rather than the old fashioned way of book sales or newspaper subscriptions. Everyone wants your eyeballs, and there is a constant nagging at every opportunity for them to drag your eyes away from this content to engage in theirs.

Attention is a driving force in the online medium, but another factor, in the world of sophisticated search and recommendation features, is fine-tuning content for the algorithm. I confess, I don’t know a damn thing about how the Medium algorithm works, but there are entire professional fields dedicated to gaming Google’s search algorithm, and Youtube channels live or die on their ability to manipulate it. This, too, is the medium becoming the message. Every new incentive – every dollar that a platform, advertiser, algorithm or consumer dangles in front of a creator to shift their content this way or that, changes the material, along with every convenience – or inconvenience – in the creative process. There are entire books written on cellphones now! Consider how different the process of writing a book is, comparing writing it by hand, writing it in a word-processor with internet access, or writing it with a cellphone. Indeed, even for paper books, now that most are also digitally available, writers are aware of how search engine friendly their content is, and how well into short, internet friendly chunks. Writers expect their books not to be read in full, but to touched lightly by the rock of human attention skipping across a vast sea of information, jumping from one place to the next.

Let’s return to Shakespeare for a second.

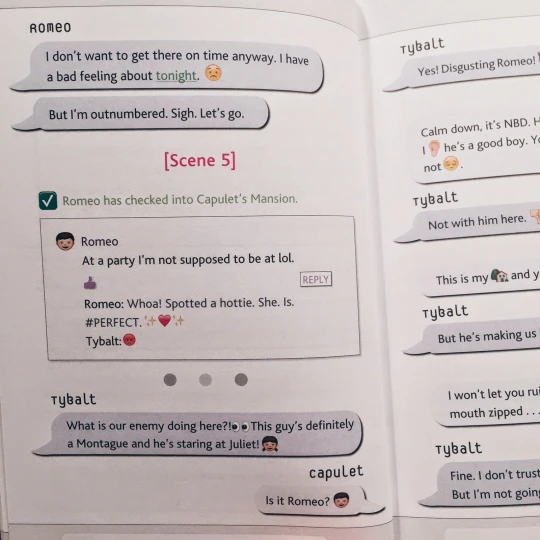

Jamie Rector, a graphic designer, took the time to summarize a series of Shakespeare plays in emojis, something I find both disgusting and delightful. Another book, by Courtney Carbone, rewrote the Bard’s plays in the format of text-messages.

Facetious as these are, they illustrate an interesting point. The message – Shakespeare’s story in this case – is meant to be the same, but the medium it’s conveyed in has altered its form almost to the point where it has become something entirely different. It’s lost something in the process, though perhaps at times it gains some new feature as well, be it humor, conciseness, or utility. For a more functional example of an Internet version of Shakespeare, let’s look at Sparknotes’ “No Fear Shakespeare”

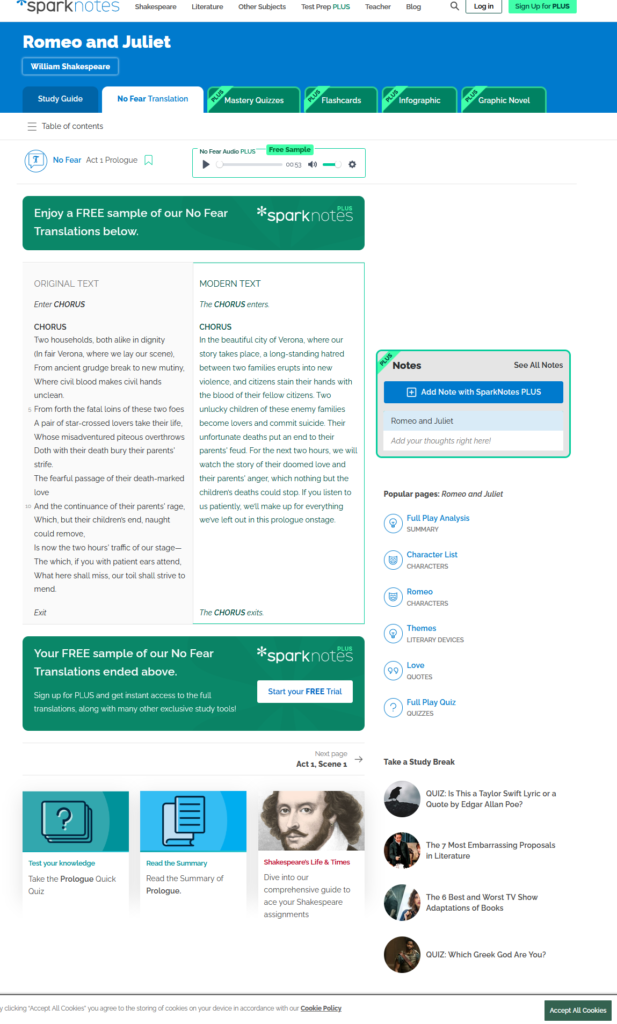

Many of us have read books with the modern translation side-by-side with the Shakespearean text in school, but that’s not all this page is. It’s hyperlinked – offering you a tantalizing choice to read a pre-digested summary of the text and its themes instead of the mentally taxing process of coming to your own conclusions. It has an audio feature, letting you hear it spoken aloud. It lets you reference the characters, and take quizzes to understand the content. It offers study guides, notes, flashcards, an infographic, even a graphic novel! It invites you to examine other subjects, it dangles completely unrelated articles before your eyes about “Which Greek God are you?” And, of course, it’s peppered with ads to pay for their service, and a query on what cookies I’d like to accept for the webpage. A quick count brought me to thirty eight choices, or calls to action before my eyes on that single page (not including the dropdowns), and only one of them was reading the text – and I think I missed a few. That’s a lot of content, a lot of decisions for you to make, and a lot of ways to study Shakespeare – or learn about Taylor Swift versus Edgar Allen Poe. I expect, within a year or two, there will also be a little AI assistant there to help answer your questions.

Is it bad? No, not intrinsically. In many ways, it’s fantastic. It’s a great tool for students who need to pass an English exam tomorrow. There’s no question there is utility here – in many ways it’s better than reading Shakespeare from a book. What you’re losing is the depth. By being able to jump from place to place, to have all your queries answered – and any that aren’t, you can plug into Google. It leaves little place for you to sit, immersed in the story, sometimes puzzled, sometimes enraptured.

Carr argues in The Shallows that the internet is affecting our ability to engage in deep, long-form attention. This is a concern that, in recent years, has grown obvious. The prevalence of platforms like Twitter and Tiktok, which emphasize short-form content, continue to feed our rapacious appetite for novelty like a perverse Skinner box. And more of us find that even sitting through a ten minute video – or reading a ten minute article – makes us antsy. If you got this far, you’re already not the average reader, and even then, chances are high you got here by skimming. I’m not judging, I do it too – most of us do, it’s what the Internet encourages.

So that brings me to an important question you should keep in mind whenever you’re reading – or really, engaging with any media. ‘Why am I engaging with this?’ Is it because you’re bored, and want to fill your coffee break? Because you want to understand it? Because you want to add a bit of genuine emotional depth to your life? Or are you cramming for an exam? The reasons why should make you stop to consider the medium you’re choosing to use. The internet – and digital media in general – is convenient, its utility is unmistakable, but that doesn’t make it inherently the best tool for the job. Sometimes there is a genuine value in sitting down with a paper book and reading it front to back, without stopping to google it whenever you have a question. Sometimes there is a real joy in trying to come to your own conclusions, or letting your curiosity linger for a little before you satisfy it with a Google query. There’s a value in boredom sometimes, too, rather than skipping from place to place, fraying your attention as it’s dragged through a mire of celebrity gossip, academic essays, sex, violence, and puppy videos.