“I could do that.”

It’s a short phrase that has been spoken by many a naive novice, looking at something that seems terribly simple, not yet wise enough to understand the menacing, underlying complexity. A fetching but simple looking oil painting seems so easy to emulate. It’s a misty blue ocean at sunset, blue and some orange, a few elegant strokes – the price of the painting is steep, so you decide to give it a go yourself.

Oh, but then there you are, selecting your paints. Was there a particular type you needed? The oil painting had been blue, but only now you realize that all those subtle hues shifted together, gently contrasting with pleasing oranges. As you sit down with your three primary colors – red, blue, and green, all one needs to make any color they like, you begin to realize that you can never produce the right hue… or, for that matter, the same hue as you had on your first attempt, inaccurate as it was. Oh, your orange has merged with the blue into a muddy mess where theirs was such a lovely gradient, now you fine your brush strokes look so harsh and bristly where they had carved an elegant clean edge.

You march back to the store, bruised but not beaten, to select once more. Now you have a hundred dollars worth of paint mixed for you, in all the colors you could possibly need. Your new brush is horse hair, whatever that does, and you even have a little spatula to carve your crisp edges. Painting over your last disaster, you try again.

Having paid the penalty for your foolishness in countless supplies, you may soon find that the cost of buying that simple painting wasn’t so steep after all. Your next effort is only mildly better, and your confidence is sorely shaken. Perhaps with some humility you conclude that it was not as easy as it looked. Perhaps this was the beginning of your journey as an oil painter, but perhaps not – either way, you encountered the discouraging truth that even seemingly simple things are often immensely difficult, with subtle complexities and countless hidden questions.

Some find this realization discouraging, others exciting, and most of us a little of both. Sometimes it’s easy to be worn down by our failed attempts, discouraged to the point that we give up on our attempts to create. Humbled, we cease to look at anything and say “I could do that.” Perhaps we begin to consider that optimism naive, or childish. There is a careful balance we all must strike here – a humble appreciation of the complexity of the world around us, and the skill of those who have mastered it in some way, is valuable. It helps us appreciate craftsmanship and ability – whether it’s that of the artist or that of the athlete. Yet we cannot let this prevent us from trying, either.

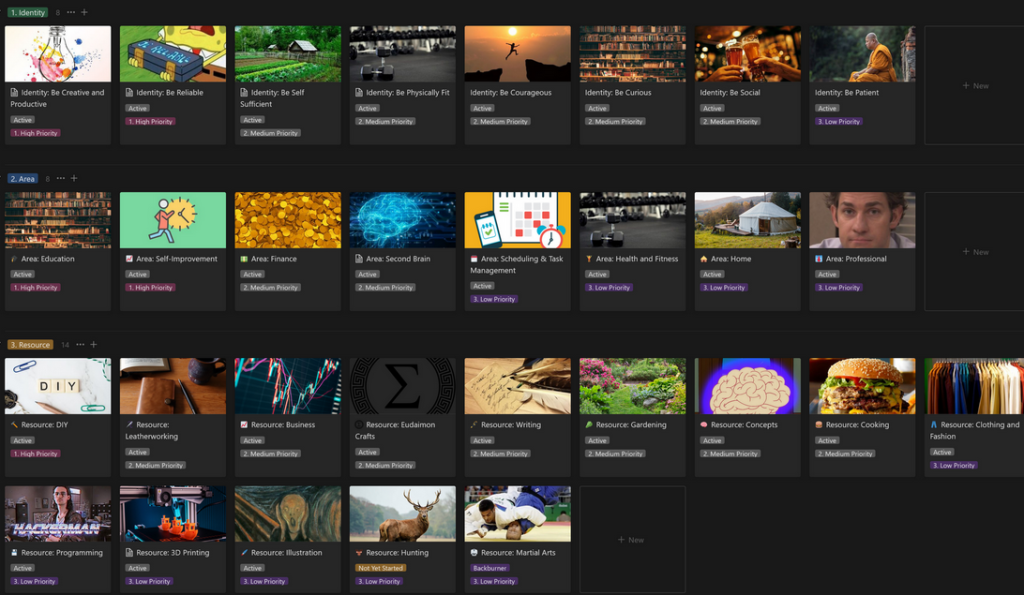

Voltaire once said “The perfect is the enemy of the good”, and the drive for perfection is what drives many away from trying. Fear of failure is intimidating enough when the criteria for failure isn’t ‘anything that isn’t the very best’. We need to accept that to become the very best at anything is an intense commitment of time and effort, but we can also recognize that in many domains, the commitment required to become pretty good at it is surprisingly low. Some are tougher than others – my journey with illustration and art has been one of several years now of – I confess – middling effort. I’m still not a pretty good artist. But my cooking journey is a younger one, and if I may be so bold, I can cook myself some pretty damn good meals, just how I like them. My proficiency at Jiu Jitsu is amateur at best, and I get absolutely dismantled by higher belts, but it only takes a few months of practice before you learn the necessary skills to protect yourself and dismantle a few newbies, yourself. It only takes a couple of months to train yourself from a completely sedentary person to somebody who can run a 10k, and there are programs to do exactly that.

Live your life with the humility to understand that some things are way harder than they look – and the courage to try it anyway. You may be pleasantly surprised at how much you can do.