It is the first of March, 1953, Moscow. A housekeeper cautiously enters the office of the most feared man on earth – lying on the ground, in urine soaked pyjamas, lays Joseph Stalin.

It was soon determined that the Vozhd had suffered a stroke – regrettably for the Soviet ruler, he had suffered it while in the midst of a brutal purge of many of the nation’s most qualified doctors. In an assumed conspiracy known as the Doctor’s Plot, Stalin’s drive to extract confessions of treason from these prisoners had been fierce. “Beat them until they confess! Beat, beat and beat again. Put them in chains, grind them into powder!” He had barked to his chief of secret police, who he felt was handling them too softly. In his final years Stalin had grown increasingly unstable, but this ruthless practice was nothing new in the Soviet Union. Nobody was safe in Stalin’s Russia. His right-hand man and most loyal servant, Vyacheslav Molotov, had seen his own beloved wife Polina sent to the Gulag for Zionist ties, and Molotov himself lived in constant fear of Comrade Stalin’s disapproval.

Stalin was removed from the floor of his office and placed on a sofa, where he laid for over twelve hours before a doctor was summoned. Stalin’s own personal physician was indisposed – he was being tortured to extract confessions and implicate others in the Doctor’s Plot. His crime had been suggesting Stalin should rest. The veracity of these confessions was not the interrogator’s concern – Stalin had wanted results. His magnates feared that if they summoned doctors without great need, they too might be implicated in this plot – people had been shot for less. When it was determined that Stalin’s life was in danger, doctors were finally summoned to treat their dying leader, before the watchful eyes Lavrentiy Beria, who had, while head of the secret police, overseen the deaths of tens of thousands. Biographer Simon Montefiore described the scene:

“At 7 a.m., the doctors, led by Professor Lukomsky, finally arrived but they were a new team who had never worked with Stalin before. They were brought to the patient in the big dining room which must have reeked of stale urine. With their colleagues under torture, they were awestruck by the sanctity of Stalin and petrified by Beria’s Mephistophelian presence lurking behind them. Their examination of the powerless, once omnipotent patient was a comedy of errors. ‘They were all trembling like us,’ observed Lozgachev. First, a dentist arrived to take out Stalin’s false teeth but “he was so frightened, they slipped out of his hands” and fell onto the floor. Then Lukomsky tried to take Stalin’s shirt off in order to take his blood pressure. ‘Their hands were trembling so much,’ noticed Lozgachev, ‘that they could not even get his shirt off.’ Lukomsky was ‘terrified to touch Stalin’ and could not even get a grip on his pulse.”

The reports of Soviet torturers carefully asking their doctor-prisoners for advice on treating strokes reads as almost satirical. As the days went by, and Stalin continued to deteriorate, Beria had his henchmen begin questioning their imprisoned doctors:

“That night, three surprised prisoners, tortured daily in the Doctors’ Plot, were led off for another session. But this time, their torturer was not interested in the Zionist conspiracy but politely asked their medical advice.

‘My uncle is very sick,’ said the interrogator, and is experiencing ‘this Cheyne-Stokes breathing. What do you think this means?’

‘If you’re expecting to inherit from your uncle,’ replied the professor, who had not lost his Jewish wit, ‘consider it’s in your pocket.’ “

Discoloured, choking on his own bile, Stalin was kept alive in torturous death-throes for as long as possible, none of his advisors willing to utter the treacherous suggestion that he be put out of his misery. On March fifth he clawed for air, raising his hand, which felt like a baleful threat to the advisors gathered around him. In his lifetime, he had amassed a tally of human death and misery perhaps only matched by Adolf Hitler and Mao Zedong. Simon Montefiore estimated that in the course of his rule “Perhaps 20 million had been killed; 28 million deported, of whom 18 million had slaved in the Gulags.”

He had been, perhaps, the most powerful and feared man on earth.

And he was dead.

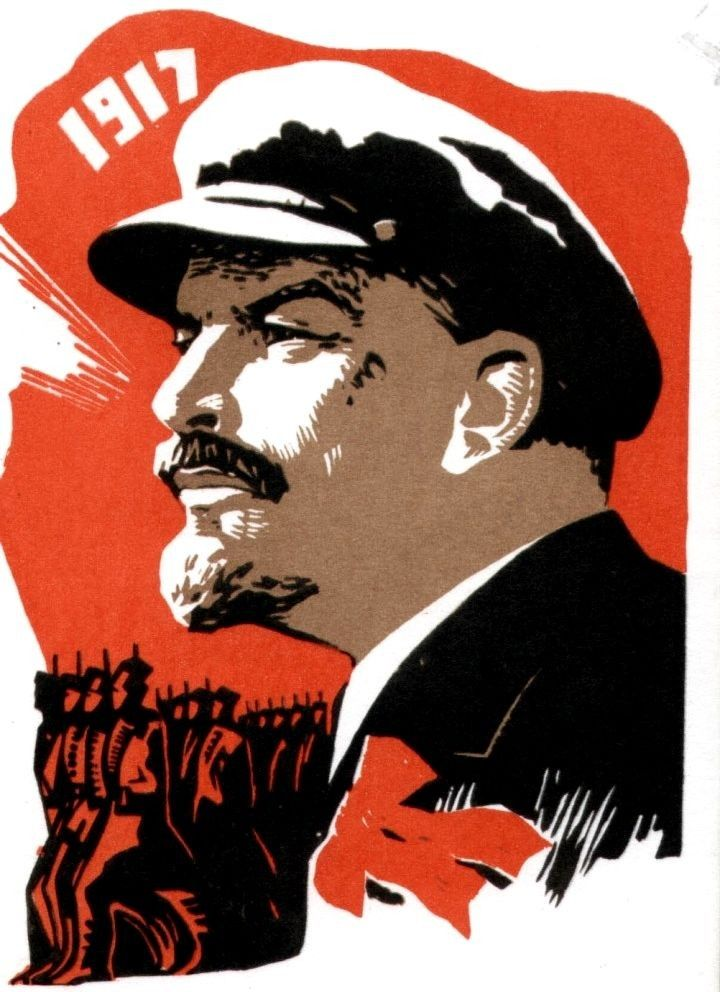

The Revolution

“There are no morals in politics; there is only expedience. A scoundrel may be of use to us just because he is a scoundrel.” – Vladimir Lenin

Joseph Stalin and his system of ruthless oppression did not emerge out of a socialist paradise. The revolution that had overseen the overthrow of the Romanov Tsars in 1917 was, after a six year civil war, eventually consolidated into the hands of Vladimir Lenin, the leader of the Bolshevik party. It was Lenin who ordered that Tsar Nicholas II, along with his entire family – including his young son and daughters – be brought into the basement of the manor they had been imprisoned in and shot. The execution was badly botched, resulting in the Tsar’s children being not only wounded by bullets, but then bayoneted, and shot in the head. Days later, other members of the Romanov family were thrown down a mine shaft, followed by hand-grenades.

Lenin next turned on his own revolutionary allies. The Mensheviks, comrades in the revolution, were violently purged in a Machiavellian consolidation of political power. Revolution was a bloody business, a business where men like Stalin could thrive. Stalin had been a brigand on behalf of the revolution during the civil war, robbing banks to finance the uprising – he would soon be promoted. Political terror was a tool well understood by Lenin, who remarked that “A revolution without firing squads is meaningless.” Stalin was a man who could pull the trigger. Following the revolution, Stalin rose to increased prominence as an efficient enforcer of Bolshevik will – dispatched to Tsaritsyn as a military commissar, he was instructed by Lenin to carry out a merciless purge. Already, while Lenin still lived, he was beginning to exterminate his political opposition among his ‘allies’ – just as Lenin had. When he arrested a group of his Bolshevik rival Leon Trotsky’s specialists and imprisoned them on a barge, it conveniently sank with all on board.

Lenin’s political terror laid ample groundwork for his successor. A secret police known as the Cheka – the “Emergency Commission for Combating Counter-Revolution and Sabotage”, was put to use rooting out rivals of the revolution. To Lenin, as he openly declared, “the state is an institution built up for the sake of exercising violence.” At least now, he proposed, that violence would be wielded in the name of the people – a dictatorship of the proletariat, a one-party state. The Cheka set to work, and instantiated a new series of concentration camps that would soon become the Gulag system.

When Lenin suffered an incapacitating stroke in 1923, he was rendered unable carry out the black business of governing a revolutionary state. He knew that he had given his enforcer too much power. He dictated a damning testament of Stalin demanding his dismissal, but it was too late. Once Lenin was dead, Stalin formed a triumvirate to oust Leon Trotsky, his most hated rival, and consolidated his own power, slowly but surely, as secretary. Trotsky was sent into exile, where he would become Stalin’s antichrist, a byword for conspiracy and intrigue, all pervasive, and a ready excuse to destroy his opposition.

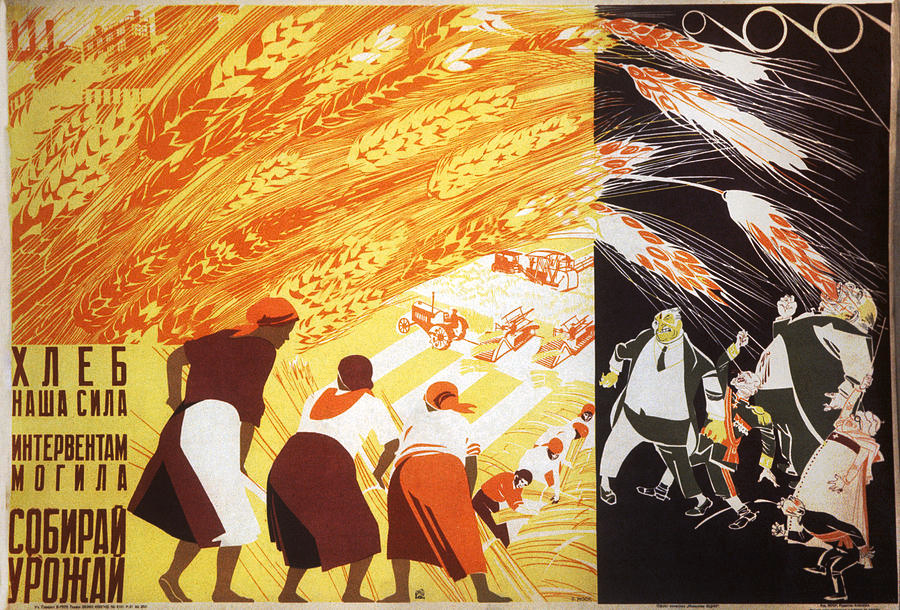

The Famine

“The peasant must do a bit of starving.” – Vladimir Lenin

During a blitz of collectivization and industrialization in the 1930s, while the Soviet state sold grain to raise money for smelters, a vast famine killed between five and ten million of its subjects.

While millions starved, Stalin holidayed in an exquisite dacha on the black sea. He took frequent holidays, though he never ceased working. Writing constant correspondences, directing, commanding, Stalin’s energy was immense. Often almost nocturnal, his comrades were forced to bend their schedules to his – often exhausted to the point of failure. In the early 30s, there were still men in government capable of questioning Stalin’s will, but that was beginning to change. His position as first among equals was well cemented, and his ability to bully and threaten to get his way became increasingly honed as his power consolidated.

Stalin’s comprehensive Gulag system began to grow as the state worked to break the peasantry. Enforcers, believing that peasants were hiding grain, were sent to search and seize food to meet their quotas. As he mulled over emptying room in the prisons to make room for the Kulaks – viciously hated as the ‘wealthy’ farmers – he scrawled in his notes:

“To allow . . . deportations: Ukraine 145,000. N. Caucasus 71,000. Lower Volga 50,000 (a lot!), Belorussia 42,000 . . . West Siberia 50,000, East Siberia 30,000 . . .”

As the famine grew worse, Stalin began to label his least efficient enforcers as ‘wreckers’ – as the Ukranian Politburo begged for food assistance as the regions reached a state of emergency, Stalin labelled the starvation as a failure of the province and a hostile act against the state. “The Ukraine has been given more than it should get”, he wrote to Kaganovich, another member of the Central Committee. He vehemently accused these officials of fabricating ‘fairytales’, despite being told of reports of trainloads of corpses pulling into Kiev. Despite his rejection of reality, -Stalin himself later confided to Winston Churchill during the war that he had to destroy “ten million [kulaks]. It was fearful. Four years it lasted. It was absolutely necessary . . .” Today it is finally coming properly to light the human cost of the Soviet Famine, and the Holodomor in Ukraine, Russia’s breadbasket, which suffered the worst from the grain quotas.

The bloody business of Soviet rule placed a considerable toll on Stalin’s enforcers, and his own family. His relationship with his wife Nadya deteriorated, and one night in 1932, she committed suicide, shooting herself. Her death affected Stalin for the rest of his life. Yet this did not distract him from his political work, which he continued to vociferously throw himself into. Stalin watched with admiration in 1934 as Adolf Hitler violently purged the Nazi party of opposition in the Night of the Long Knives – “Did you hear what happened in Germany? Some fellow that Hitler! Splendid! That’s a deed of some skill!” His comrades in government may have exchanged nervous glances – the worst was yet to come.

The Terror

“Beat, destroy without sorting out… if during this operation, an extra thousand people will be shot, that is not such a big deal.” – Nikolai Yezhov, head of the NKVD

To Stalin, terror was not an accidental byproduct – it was baked into his rule, to leave every person at every level of power in constant fear that they might be next. Even if one, with an excess of charity, ruled that Stalin was not responsible for the great famines of the 1930s, the deliberate political terror he inflicted upon every echelon of his society is not in doubt. Political murder in the Soviet Union was done by callous quota. The Politburo, of which Joseph Stalin was prince, drafted and distributed lists of mandated arrests and killings for their regions. While individuals were often singled out for arrest and murder, many more were unfortunate enough to be mere statistics. Stalin is often attributed with a bleak and callous quotation, “A single death is a tragedy; A million deaths is a statistic.” Whether it came from his lips or not, it speaks to the sort of man who could, along with his Politburo, sign his name to the death warrants of 36,000 people, and utter the words, “Better an innocent head less, than hesitations in the war.”

The enemy now, as it had been in Lenin’s time, were counter-revolutionaries and “wreckers”, saboteurs who were wilfully attempting to ruin the communist quest for utopia. Their supposed sabotage – carried out by anyone had been a constant thorn in the side of the state during the drive for collectivization and industrialization. Yet there was another insidious foe. Leon Trotsky, once a hero of the revolution, seemed to lurk in the shadows beneath every bed. A perennial bogeyman, responsible for every failure of the Soviet project, seemingly limitless in his capacity to infiltrate the state at its highest levels. Everywhere, prisoners were confessing to their involvement in this Trotsky led conspiracy. Lev Kamenev and Grigory Zinoviev, the triumvirs who had helped Stalin oust Trotsy in the 20s, were themselves implicated in this new great trial.

“’You think Kamenev may not confess?’ Stalin asked Mironov, one of Yagoda’s Chekists.

‘I don’t know,’ replied Mironov.

‘You don’t know?’ said Stalin. ‘Do you know how much our State weighs with all the factories, machines, the army with all the armaments and the navy?’ Mironov thought he was joking but Stalin was not smiling. ‘Think it over and tell me?’ Stalin kept staring at him.

‘Nobody can know that, Joseph Vissarionovich; it is the realm of astronomical figures.’

‘Well, and can one man withstand the pressure of that astronomical weight?’

‘No,’ replied Mironov.

‘Well then . . . Don’t come to report to me until you have in this briefcase the confession of Kamenev.’ “

Lenin’s Cheka was replaced by a new secret police force, the NKVD, headed by Genrikh Yagoda. Yagoda oversaw these show trials of Trotskyist “wreckers”; both Kamanev and Zioviev were shot. The torturers and killers knew, as well, that innocents were to be sacrificed to this meat grinder. The henchmen referred to torturing an innocent man as frantsukaya borba, “French wrestling.” They had little choice in the matter. Yagoda was himself executed as a Trotskyist in 1938 – if even the head of the NKVD could be executed, they certainly could be as well.

Nikolai Yezhov was instated as Yagoda’s replacement, and he had quotas to fill. Regional leaders, anxious not to draw suspicion on themselves by dragging their feet, often exceeded their quotas. To avoid suspicion, every man from the top to the bottom had to prove his loyalty. Nikita Khruschev, who would later become First Secretary after Stalin’s death, himself not only met but exceeded his quota of shootings – ordering the death of 55,741 officials, over 5000 more than required by the Politburo. The frenzy of the Terror was made worse by the fact that the perpetrators knew that they could be next – each man taken to the torture chamber produced new lists of potential traitors, and even a hint of suspicion was enough to warrant interrogation.

Old Bolsheviks, heroes of the revolution that had brought Lenin to power, had often done a tour of the Russian Tsar’s Katorga prisons, which laid the foundations for the Soviet gulags. In 1916 there were fewer than 30,000 prisoners – by the time of the USSR, they routinely held up to two million at a time. Under Stalin, over 30,000 camps were administered – as many camps as there had been prisoners under the Tsars – and under his auspices they were used for slave labor. One of the prisoners, still possessing his Russian wit, remarked: “At last the dreams of our beloved Czar Nicholas, which he was too soft to carry out, are being fulfilled. The prisons are full of Jews and Bolsheviks.” One camp, deep in the ruthless Siberian winter, reported a death rate of 97% of its inmates – when a camp administrator was warned that people in the camps might die, the answer was clear: “We are not trying to bring down the mortality rate.”

The Old Bolsheviks, loyalists of Lenin, were a dying breed. Stalin’s new Terror, and the unravelling of this Trotskyist plot, exterminated many of his potential opponents. Nikolai Bukharin, head of the right opposition, had been shot. Kamenev and Zinoviev had been shot. Trotsky was an arch-traitor, soon to be assassinated by an ice-pick to the back of his skull. In this environment of terror, chief administrators were themselves in constant fear of arrest. Fyodr Eichmans, one Gulag chief, and his two immediate successors, were all executed in the span of two years. Nikolai Yezhov, near the very center of the murderous web, was himself arrested. In February 1940 he was dragged into a bloodstained basement where prisoners could be killed in secret, and shot. With Yezhov as scapegoat, Stalin took the opportunity to pass the blame onto his secret police chief, and abdicate his own responsibility for the brutal political terror that had consolidated his rule.

The War

“I order that anyone who removes his insignia . . . and surrenders should be regarded as a malicious deserter whose family is to be arrested as a family of a breaker of the oath and betrayer of the Motherland. Such deserters are to be shot on the spot. Those falling into encirclement are to fight to the last . . . those who prefer to surrender are to be destroyed by any available means while their families are to be deprived of all assistance.”- Joseph Stalin, Order No. 270

In June 1941, Adolf Hitler launched Operation Barbarossa, the largest land offensive in human history, invading the Soviet Union in an attack that deeply shocked Stalin. Despite clear evidence of a mounting German invasion, Stalin had been vociferous in his denial that Hitler would attack in 1941 – and when he did, the Soviet state nearly collapsed. The German offensive pressed deep into Russian territory, and Stalin seemingly resigned himself to what he considered inevitable – a coup d’etat within the Soviet state. The Vozhd, convinced that he would be the next to be put against the wall and shot, as countless members of his own party had been under his watch, isolated himself and awaited his fate. Perhaps he underestimated how deeply he had tormented his comrades – either out of complete terror, or out of idealistic loyalty, his magnates refused to replace their leader as the German Panzers advanced upon Moscow.

In the four-year span of Hitler’s war with Russia, an estimated 30 million people died, including 9 million children. The Soviet Union was ill-prepared for a war with Germany, having only recently brutally purged its own military to ensure that none could challenge Stalin’s power. In a black irony that would later be matched by tortured doctors being questioned to diagnose Stalin’s stroke, many officers were released from the gulag for the purpose of repelling Hitler’s assault. While some were liberated from their prisons to fight the war, many others were condemned – Stalin was merciless to those he considered cowards or traitors, and soldiers who retreated or fell into enemy hands could expect no sympathy from the Soviet state. In a desperate attempt to halt the complete collapse of the front, he approved Order No. 270, permitting the punishment not only of captured soldiers, but their families as well.

When his own son Yakov was himself captured, Stalin cursed, “The fool—he couldn’t even shoot himself!” In retribution for his son’s supposed cowardice, Stalin had his own daughter-in-law, Julia, arrested. From 1941 to 1942, nearly 1,000,000 Russian servicemen were condemned by their own government, and an estimated 157,000 were shot. The equivalent of fifteen divisions of Russian fighting men were executed by their own state – more would be sent to the gulags when the war ended.

Perhaps the most famous battle of the Eastern front was the one that shared the Vozhd’s name – Stalingrad. In this industrial city on the Volga the Soviet Union fought tenaciously to hold and then repel the German advance. The titanic struggle for the city reduced it to rubble, as hundreds of thousands of men fought bitterly in the ruins. The Germans called it Rattenkrieg, rat warfare. “Not a house is left standing,” a lieutenant wrote home, “there is only a burnt-out wasteland, a wilderness of rubble and ruins which is well-nigh impassable.” During the battle of Stalingrad alone 13,500 Russian soldiers were executed by their own leadership. Soldiers and citizens alike were warned with Stalin’s quotation of Lenin: “Those who do not assist the Red Army in every way, and do not support its order and discipline, are traitors and must be killed without pity.”

After years of bloody warfare, the tides began to turn on the German army. Repelled at Stalingrad, vanquished at Kursk, and pushed into retreat, the Russians pursued. As Stalin received reports of mass rape – two million German women would be raped – his answer was predictably callous. “You have of course read Dostoevsky? Do you see what a complicated thing is man’s soul . . . ? Well then, imagine a man who has fought from Stalingrad to Belgrade—over thousands of kilometres of his own devastated land, across the dead bodies of his comrades and dearest ones? How can such a man react normally? And what is so awful about his having fun with a woman after such horrors?”

After the full collapse of the German Reich, Stalin had cause to celebrate. While he had drank little during the war, now he began to often become blindingly drunk. Simon Montefiore gave one account of Stalin’s cruel sense of humor, even among other world leaders. Entertaining Charles de Gaulle in a diplomatic banquet in 1945:

“Stalin, swigging champagne, took over the toasts from Molotov. After praising Roosevelt and Churchill, while pointedly ignoring de Gaulle, Stalin embarked on a terrifying gallows tour of his entourage: he toasted Kaganovich, ‘a brave man. He knows that if the trains do not arrive on time’—he paused—’we shall shoot him!’ Then: ‘Come here!’ Kaganovich rose and they clinked glasses jovially. Then Stalin lauded Air Force Commander Novikov, this ‘good Marshal, let’s drink to him. And if he doesn’t do his job properly, we’ll hang him.’ (Novikov would soon be arrested and tortured.) Then he spotted Khrulev: ‘He’d better do his best, or he’ll be hanged for it, that’s the custom in our country!’ Again: ‘Come here!’ Noticing the distaste on de Gaulle’s face, Stalin chuckled: ‘People call me a monster, but as you see, I make a joke of it. Maybe I’m not horrible after all.’

The Peace

“Ideas are more powerful than guns. We would not let our enemies have guns, why should we let them have ideas?” – Joseph Stalin

Stalin’s power and prestige following the war was unrivalled – yet his paranoia remained. As he grew older, and the matter of his succession more relevant, the aging Vozhd seemed ever more unstable. Molotov, one of his oldest and most loyal comrades, remarked that “His last years were the most dangerous. He swung to extremes.” Stalin, an avid lover of film, assumed responsibility for reviewing Russian cinema to ensure it was appropriate. Increasingly reclusive and isolated, he began to believe his own propaganda. Montefiore noted:

“Stalin imposed politics on film but also film on reality. Djilas noticed how he seemed to mix up what was going on ‘in the manner of an uneducated man who mistakes artistic reality for actuality.’ He revelled in films about murdering friends and associates. Khrushchev and Mikoyan repeatedly sat through a British film, no doubt one of the Goebbels collection, about a pirate who stole some gold and then, ‘one by one,’ killed his accomplices to keep the swag.

‘What a fellow, look how he did it!’ exclaimed Stalin. This was ‘depressing’ for his comrades who could not forget that, as Khrushchev put it, ‘we were temporary people.’ Stalin’s isolated position made these films increasingly powerful. After the war, Stalin wanted to impose taxes on the peasants even though the countryside was stricken with famine. The whole Politburo sensibly opposed this, which angered Stalin. He was convinced the peasants could afford it: he pointed to the plenty shown in his propaganda movies, allowing him to ignore the starvation.”

Khruschev’s feeling that they were temporary people was hardly unreasonable. Even the generals of the war, lionized only a few years earlier, were quickly cast aside. Marshal Kulik was quietly shot in 1950 after grumbling about politicians stealing credit from the soldiers. Georgy Zhukov, arguably Stalin’s most able general, was expelled from the party, demoted, and sent to the Urals. Even Stalin’s own family feared and mistrusted him – for good reason, as he had proven time and time again that even they were not safe. His beloved daughter Svetlana – one of the few people in Stalin’s life who he showed tenderness -was often eager to escape her visits with him. In a letter to his daughter, Stalin shows a small measure of humanity, sending her some tangerines he had grown himself. ‘Hello Svetka . . . It’s good you haven’t forgotten your father. I’m well . . . I’m not lonely. I’m sending you some little presents— tangerines. A kiss.’ Yet to another of his advisors, he muttered, ‘While everyone talks about the great man, genius in everything, I have no one to drink a glass of tea with.’

Some of his only interaction was in the often gruelling marathon drinking and film-watching sessions he subjected his top magnates to. Inviting them to frequent nocturnal drinking sessions that ran well into the morning, they were expected to drink heavily – abstaining was not an option. Nikita Khruschev, who would soon inherit Stalin’s empire, remarked, ‘A reasonable interrogator would not behave with a hardened criminal the way Stalin behaved with friends at his table.’ Whether he suffered a heavy conscience for his actions or not, Stalin was still haunted by the ghosts of his past. In his unassailable place as dreaded Generalissimo, he could no longer build genuine relationships with his courtiers, or even his family, tainted as they all were with the all pervasive threat of exile, torture, and death. He was forced to put up with disingenuous grovelling or fearful evasiveness at every attempt to form a relationship or nominate a successor – yet his constant short temper, paranoia, and cruelty made it inevitable. Stalin was right to be paranoid, as well, as many of his most capable advisors, like Laverntiy Beria, had begun to bitterly hate him. Beria, who had served as Stalin’s spymaster, had begun to fall out of favor – but he was still likely the second most feared man in the Soviet Union. Many soviet generals during the war coined a dark euphemism, “Coffee with Beria”, to mean the arrest and torture of another comrade.

On the first of March, 1953, Stalin suffered his stroke. Four days later, he was dead. To this day it is an open question whether he was assassinated – Beria certainly had ample cause and ability to arrange such a murder, and even supposedly boasted to Molotov and Kaganovich, “I did him in! I saved you all!” Despite his careful political positioning to succeed Stalin, he was soon outmanoeuvred by Khruschev and his allies, who swiftly had him shot for his vast contribution to Stalin’s murderous secret police.

The Legacy

“Every Communist must grasp the truth: ‘Political power grows out of the barrel of a gun.'” – Mao Zedong

The communist world was shocked in 1956 when Stalin was denounced by his inheritor, Nikita Khruschev, in what would be known as “The Secret Speech”. In the Soviet Union a process of “De-Stalinization” would follow, as his cult of personality was dismantled. Yet Stalinism endured – in China, the revolutionary leader Mao Zedong continued to model his rule strongly on that of Stalin, and China would experience much the same brutal suppression as Russia. In North Korea, Kim Il Sung adopted similar ruthless systems of oppression, which remain in the hands of his dynasty to this day.

We can learn much from Stalin’s rule, as a lesson of a political future we dearly wish to avoid. But we ought also to remember that Stalin’s ruthless rule had acted as an idealistic model for many rulers since. As vicious a man as he was, it pays to remember that terror and cruelty have proven to be effective tools in controlling a society, and for all the brutality, Stalin dragged his state into an industrial powerhouse that could contest with Germany, and then the United States. Still, we must take great care not to let these tools of terror be wielded upon us, even with the promise of future utopia. The torturers of the Soviet Union were not exceptional men – they were simply men.

At the helm of all of this – the decades of famine, torture, war, and terror, was a man. Joseph Stalin was not a devil, but a human being, a master of deceit, control and fear, who stood behind the levers of a brutal machine of state. He was the product of a bloody struggle for power where those without the will to brutality were imprisoned and exterminated. He was also not alone. Working for him, and with him, were countless other men and women. Lavrentiy Beria, such a deadly and murderous spymaster, could have been a different man. A man “one could imagine becoming Chairman of General Motors,” His daughter-in-law later remarked.

Many of us think that we would stand up to this brutal regime. Some of us have the modesty to admit that we don’t know if we could. It takes a dark degree of insight to understand, without an indictment on your own character, that you could have been submitting to Comrade Stalin your own report of the thousands killed under your auspices – perhaps out of fear for your family’s safety, and yet, perhaps, with a sense of ideological pride, contempt for your victims, or ambitious relish, as well. Perhaps you would have lacked the courage to stand up to the brutal regime, or you would have felt it was no good to try. To know that you could be the Chekist torturer savagely beating yet another political prisoner to extract a confession, or the prisoner himself – or perhaps both, in the very same lifetime. Humans did this. Humans fought for the Soviet Union, shot the Romanovs, built and filled the Gulags. They tortured, and were tortured. They built the Berlin wall, and they tore it down. As Stalin’s Russia creeps ever further into the dim light of history, we may be tempted to view it as a thing of the past, but these humans were our great grandfathers – and states such as North Korea live in the shadow of Stalinism to this day. If we fail to understand that we are capable of the same brutality, we are fated to relive it, perhaps next on an even more malignant scale. As our technology and society grows ever more sophisticated, so does our capacity to truly create hell on earth – remember that.

Citations:

Stalin – Simon Sebag Montefiore

The Romanovs – Simon Sebag Montefiore

The White Pill – Michael Malice

Stalingrad – Antony Beevor