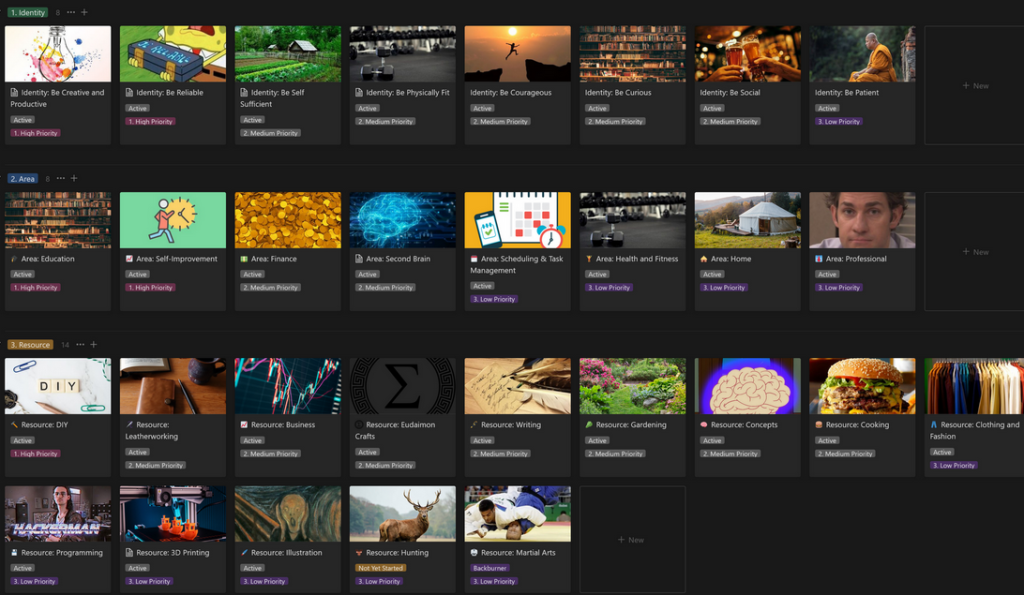

I used to consider the ability to read a lot of books a good in and of itself. I kept a list of every book I finished, and set myself reading goals of finishing 3 or 4 a month – child’s play for some of our more prodigious readers out there. Today I want to explore some of the issues one can encounter when one focuses too much on the goal of reading a lot and not enough on the goal of actually learning anything. I’ve known for a long time that some of my study was higher quality than others. In the end, I found there were a few calibres of studying a book:

- Slam through a book, sometimes very quickly, call it done, and never look at or think about it again.

- Highlight as you go, and then ignore the highlights.

- Highlight as you go, then give the highlights a quick reread at the end.

- Highlight as you go, take notes, and consolidate the notes into one place.

- Put things into your own words – refine the notes into key takeaways and principles, and connect the knowledge to other material.

As well as a few post-reading steps:

- Review the material (rereading notes, talking to someone about it, etc).

- Produce something (besides notes) or otherwise put the knowledge into action.

- Reread the book entirely.

As the list progresses from top to bottom of the first list, I found most of my reading fell into category 2, and it was rare I did any of the post-reading things. I do most of my reading digitally and those highlights are captured, saved in Readwise, and sent to Notion, so the work does produce some good reference material if and when I need it. Yet I found that on the whole, if someone were to quiz me on what I learned reading throughout the month or year, I’d be hard pressed to tell them unless I could review my highlights. I had collected information, but I’d outsourced my memory to my digital system, and my brain had quite rationally decided it would rather save space for something else. And besides, if I didn’t produce anything or put anything into action, what was the point? Reading for its own sake can be pleasurable, and if that’s the goal from the outset so be it, but many of us read with the goal, or at least the perception, that we are reading in order to learn something new or otherwise improve ourselves.

The past month I’d been studying a lot of stoicism. In a sense I did get once again trapped in the ‘high volume’ trap of slamming through Seneca, Marcus Aurelius, and Musonius Rufus, as well as Ryan Holiday and William Irvine’s more modern works, but this time I was beginning with an end in mind. I’d read these philosophers before (with the exception of Rufus), and this time I was specifically looking to find knowledge to put into practice, to inform my ideas of virtue and living well. Having read them before I already had my initial appraisal that I approved of the philosophy, and the act of rereading proved to be a valuable experience that I had often neglected. I considered rereading a book to have a high opportunity cost – instead of reading something new, which could potentially give me new knowledge and insights, I was reading something I ‘already knew’. But as it happens, unless you have a perfect memory, the odds that you ‘already know’ the content of a book you’ve only read once and never reviewed are next to zero. Knowing the core concepts of a book and then re-reading it, or at the very least reviewing any notes you took, act as a method of spaced repetition that improves retention. Not only that, but it refines the insights you find truly valuable – I often find on my second reading I care less for the general summary of the book and appraising its value, which I often at least vaguely recall, and instead I search for the specific insights of true value to me.

And, as a matter of fact, Seneca had several insights on this topic that made me reflect on my study habits. Seneca, in writing to his friend Lucilius, advised him that his desire for greater breadth of reading may have been getting in his way, rather than aiding him in his quest for wisdom:

“The primary indication, to my thinking, of a well-ordered mind is a man’s ability to remain in one place and linger in his own company. Be careful, however, lest this reading of many authors and books of every sort may tend to make you discursive and unsteady. You must linger among a limited number of master-thinkers, and digest their works, if you would derive ideas which shall win firm hold in your mind. Everywhere means nowhere. When a person spends all his time in foreign travel, he ends by having many acquaintances, but no friends. And the same thing must hold true of men who seek intimate acquaintance with no single author, but visit them all in a hasty and hurried manner.”

I realized that certainly, in my reading adventures, I had many acquaintances and few friends. I’d read a lot, but how many could I call on and trust in? Very few. The Stoics were one, and a selection of other formative authors had strongly influenced my thinking, but I could easily say that a majority of the reading list I’d proudly cultivated were diversions. Today, our access to information is so vast that we can drink from the fire-hose whenever we like – and even when we’d rather not. Even when reading the ancients, such as the Plato, Aristotle, or the Stoics, we’re given a vast selection of translations, interpretations and secondary sources to choose from. Nicholas Carr, in his book The Shallows, identifies an incipient peril in our modern mode of information consumption: “And what the Net seems to be doing is chipping away my capacity for concentration and contemplation. Whether I’m online or not, my mind now expects to take in information the way the Net distributes it: in a swiftly moving stream of particles. Once I was a scuba diver in the sea of words. Now I zip along the surface like a guy on a Jet Ski.”

Carr’s book, exploring the effects the internet has on our brain, strongly points to the fact that while we are granted access to considerably more information than ever before, our ability to truly learn information is in peril. We do not concentrate, we do not contemplate, we rarely digest, we simply consume. Some of us consume until we’re sick, utterly anxious and paralyzed by torrents of information – most of it irrelevant to us at best and often even dangerous to our well-being. A brutal murder in another country, a political scandal we have no control over, a snake-oil salesman persuading our fatigued minds to buy yet another thing. And even the valuable knowledge – hyperlinked, constantly dragging us from place to place, rendering us unable to sit and actually think about what we’d read before. The ability to index documents and search for key terms brings us to exactly the sweet morsel we’re looking for, at the expense of nutritious meal that morsel had been previously embedded in.

Carr uses an interesting metaphor for the transfer of information out of our working memory – which can generally only hold limited information for a short period of time – into long-term memory.

“Imagine filling a bathtub with a thimble; that’s the challenge involved in transferring information from working memory into long-term memory. By regulating the velocity and intensity of information flow, media exert a strong influence on this process. When we read a book, the information faucet provides a steady drip, which we can control by the pace of our reading. Through our single-minded concentration on the text, we can transfer all or most of the information, thimbleful by thimbleful, into long-term memory and forge the rich associations essential to the creation of schemas. With the Net, we face many information faucets, all going full blast. Our little thimble overflows as we rush from one faucet to the next. We’re able to transfer only a small portion of the information to long-term memory, and what we do transfer is a jumble of drops from different faucets, not a continuous, coherent stream from one source.”

In that excerpt, Carr mentions ‘Schemas’, and strong schemas, I believe, are the core of wisdom. Our cognitive schemas are essentially our edifice of thought, the way we categorize information. Stereotypes are schemas, and as we know, these things can at times be extremely valuable, and at other times prove horribly detrimental, if poorly constructed. Our schema of a dog will influence how we interact with that dog, as will our schema of justice influence how we interact with other people. If our schemata of things like ‘virtue’ or ‘politics’ are not formed by careful contemplation, they will be formed for you by the fire-hose – scatter-shot, unreliable, contradictory, and alienating.

Seneca, in his letter to Lucilius, goes on to say:

“Accordingly, since you cannot read all the books which you may possess, it is enough to possess only as many books as you can read. “But,” you reply, “I wish to dip first into one book and then into another.” I tell you that it is the sign of an overnice appetite to toy with many dishes; for when they are manifold and varied, they cloy but do not nourish. So you should always read standard authors; and when you crave a change, fall back upon those whom you read before. Each day acquire something that will fortify you against poverty, against death, indeed against other misfortunes as well; and after you have run over many thoughts, select one to be thoroughly digested that day.”

So digest. Concentrate. Contemplate. It’s hard work, much harder work than simply skimming the surface, but it’s necessary for the development of genuine knowledge, rather than the caricature that a large bookshelf might imply.

Works Cited:

Carr, Nicholas. The Shallows: What The Internet Is Doing To Our Brains. Reprint edition. New York: WW Norton, 2011. Amazon Link

Seneca, Lucius Annaeus. Letters from a Stoic: The Ancient Classic. Capstone Classics. Chichester: Capstone, 2021. Amazon Link